You’ve got a new smartphone and while setting it up, you are faced with the Terms and Conditions. You click agree without reading them.

Sound familiar? This common scenario illustrates how people treat contracts in everyday life. Many people view the contract as a necessary hoop to jump through on the path to a goal, whether that be using a product, or securing a deal at work.

Project work in the construction industry is typically underpinned by a chain of contracts between clients, contractors and subcontractors. Often it is only when something goes wrong that the contract takes on a bigger significance. However, unfortunately, at this point it can be a little too late. Although your lawyer will endeavour to provide you with the best available options for action in the circumstances, those options will be limited by the contract that was signed at the start of the deal.

In our experience, it is much easier and more cost-effective for parties to allocate an appropriate level of time and resources to properly drafting and negotiating the contract at the outset of a project. This may help avoid costly litigation should a dispute arise further down the track. That’s why we always advise parties to seek legal advice – whether from Civic Legal or another law firm – before signing a contract.

To illustrate these principles and give you some practical guidance, we will examine some clauses in more detail below. For the purposes of this article, we will use indemnity clauses as an example.

What is indemnity? Indemnity (against something) is protection against loss or damage, especially in the form of a promise to pay for any loss or damage that occurs.

Why are indemnity clauses so prevalent in construction or infrastructure contracts? Because they give greater protection to the indemnified party to a contract than the ordinary law of negligence (and the indemnified party managed to negotiate or demand such a clause).

One difference between reliance on an indemnity clause and reliance on the law of negligence lies in the requirement to prove fault: under the law of negligence, one party must prove the other party was at fault in order to recover compensation for loss or damage. However, under an indemnity clause, the indemnifying party must pay for the loss or damage whether or not they were at fault.

Another difference lies in recovering costs. Under the law of negligence, if you have suffered loss or damage and sue the other party and win, the court may order them to pay your costs (typically your legal fees). However, the Supreme Court operates on a costs scale, by which the other party only pays a certain proportion of your costs.

Say the award amounts to, say, 50% of your true costs, that then leaves you out of pocket for the remaining 50%. However, under indemnity clauses, the indemnified party would be entitled to recover virtually 100% of their legal costs.

There are other detailed aspects of indemnity clauses but overall, the main point to understand is that indemnity clauses exist to give the indemnified party greater legal protections than would otherwise be available to them.

If something goes wrong and the indemnified party suffers losses, the indemnifying party will cover the full extent of the loss, almost as if the indemnifier were acting like an insurer.

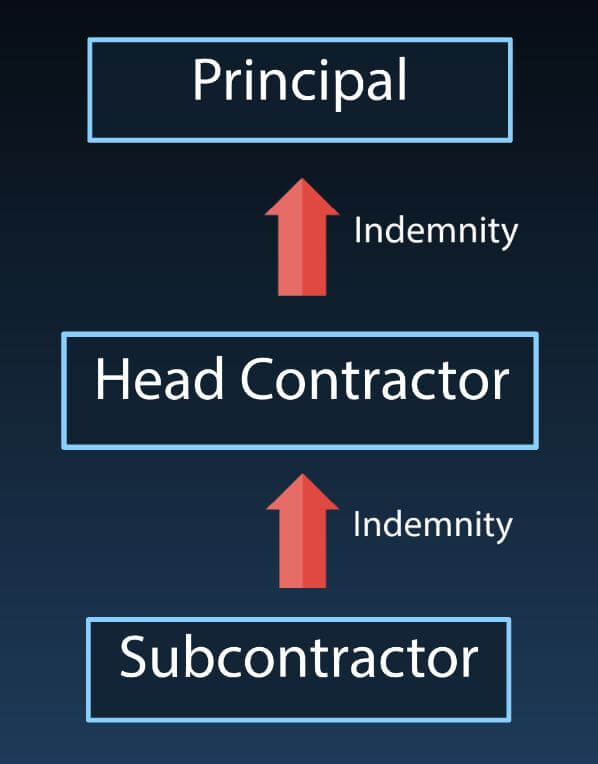

In the construction industry, the chain of indemnities typically looks like this:

The head contractor indemnifies the principal in their contract, and passes this ‘down the chain’ to their subcontractors.

Take, for example, a property developer (the principal) who is building a 500-room luxury hotel. One of the subcontractors installs lifts which are the subject of indemnity clauses.

Let’s say that after practical completion and the commencement of the hotel business, the lifts fail and are to be out of operation for one month. This comes to the attention of tour operators, who then cancel bookings for their tour groups from China for two months as a precaution.

As a result, the hotel loses the substantial revenue that it would otherwise have earned during those two months.

If the hotel loses profits of say $2 million over those two months, the owner could look to recover those losses from the head contractor under the indemnity clause in the head contract. The head contractor could then turn to the subcontractor to recover the same under the indemnity clause in the subcontract.

The goal of the principal is therefore to protect itself from losses by relying on the indemnity clause in the head contract and similarly the goal of the head contractor is to protect itself from losses attributable to the subcontractor.

Indemnity clauses can be broken down into two main components: the indemnity, and the exclusion. In the next section, we will explain some things to look out for in both parts of indemnity clauses in construction contracts.

One might think that all indemnity clauses have the same goal and therefore will be the same as each other.

Let’s have a look at some examples to see if that is the case. The following are a couple of indemnity clauses from actual contracts:

Example 1

“The Contractor will indemnify the Company from and against any and all liabilities suffered by the Company howsoever caused…”

Example 2

“The Contractor will indemnify (and will keep indemnified) the Company from and against any and all liabilities suffered by the Company and arising out of the performance of the contract…”

The decided cases show that the type of clause in Example 1 would operate more broadly than the clause in Example 2, which would be restricted to such liability as would arise from the performance of the contract. However, the additional words “and will keep indemnified” potentially extends the obligation beyond the life of the project and well into the future.

Often, indemnity clauses are qualified by an exclusion clause. A subcontractor finding itself in on the receiving end of a claim by the contractor may seek to rely on such an exclusion to reduce its liability. Given the nature of indemnity clauses, it may be the only protection from full liability available to the indemnifying party. It is therefore worth paying attention to this aspect.

Let’s have a look at a few examples.

Example 1

“The Subcontractor’s liability to indemnify the contractor will be reduced in proportion to the extent that a negligent act or omission of the Contractor contributed to its loss or damage”

This clause is relatively measured and proportionate. It enacts the fairness of reducing the subcontractor’s liability where the contractor was partly at fault. It could have limited the contractor’s liability only to the situation where the contractor was wholly at fault, and yet it does not. This is a fair clause.

Example 2

“The Subcontractor will not be liable to the extent that the liability was solely caused by the Contractor’s negligent act or omissions”

By contrast, Example 2 looks as if it seeks to achieve fairness, but then limits the reduction of liability to the situation where it was caused “solely” by the contractor. However, in reality, it will be very difficult to isolate fault to just one party and therefore the subcontractor could potentially reduce liability in only a tiny number of instances using this exclusion.

Example 3

“The Subcontractor will not be liable to the extent that the liability was solely caused by the Contractor’s wilful misconduct”

Example 3 is even more restricted. How often does one see wilful misconduct causing damage on a worksite?

Example 4

“The Subcontractor will not be liable to the extent that an act or omission of the Contractor may have contributed to the loss or damage.”

Example 4 would seem to be less harsh than the others. It allows for the possibility that the contractor “may” have contributed to the loss. IF that possibility exists, the subcontractor would have a reasonable basis for reducing liability under the indemnity clause. This is a clause that looks fair to both parties. This clause is the most favourable to the subcontractor out of these four examples.

Some contracts might not even have an exclusion clause. The result is that there is little or no scope for reducing the indemnifier’s liability in the event a claim is made under the indemnity clause.

At Civic Legal, we have seen some contracts that are hundreds of pages long. We have also seen contracts that are scribbled on the back of a piece of paper in illegible handwriting. Contracts come in all shapes and sizes, and there is a huge variation in the types of clauses that may be included.

As a result, the impact that a contract has on the parties to it varies significantly. Often, you have to look at both the detail in the wording of specific clauses (as illustrated above), as well as the contract as a whole and how it all fits together, in order to fully understand its legal implications to your business.

Never pass up the opportunity to negotiate the terms of your contract at the outset of a project. It is also always better to get advice before entering into the contract. Doing these things will give you more control over the management of your contracts.

Managing Principal

9200 4900

Disclaimer: This article provides a general summary of subject matter and does not constitute legal advice. The law may change and circumstances may differ. Therefore, you should seek legal advice for your specific circumstances.